One of my favorite things about being a naturalist is the feeling of being “in tune” with nature. That ability to look at which plants are blooming, or hear which birds are singing, and know exactly what season, month, or maybe even week it is. (You know, like when you see snow on the ground and know it’s winter!) Seriously though, have you heard chickadees singing their “phee-bee” song lately? That is a lovely noise signaling longer days despite it being quite cold out. I’m also “tuned in” just by answering the phone at Maine Audubon: Knowing it is fall/winter, and sometimes which trees are over-producing seeds based on what birds are reported “missing.”

Keep in mind, a lack of birds in your yard or at your feeder may be due to a variety of factors, including: food availability, presence of predators (especially cats), time of the year, or even just the time of the day. This post is going to look at a few species that are having atypical winters in Maine, and highlight a few of the resources we use to keep track.

Finches

This winter was predicted to be good for our irruptive finches, species including: Common Redpolls, Purple Finches, and Pine Grosbeaks. They were expected to come south into Maine for the winter because of a lack of food in their typical winter ranges across the boreal forest. It has really been a mixed bag of results for those though. Common Redpolls are in Maine in higher-than-average numbers but the bulk seems to be stalled north of Augusta. Redpolls typically arrive in Maine late in the winter so we may see more in the coming weeks. Purple Finches are scattered around the state following an above-average push last fall (similar to the flight in 2016). We haven’t seen a good movement of Pine Grosbeaks since the winter of 2012/13, and while this year isn’t as large, they are being seen state-wide. These grosbeaks, along with other finches, seem to be preferring ash (Fraxinus) seeds compared to past years when they are more common feeding on fruit-bearing trees.

Blue Jays

There was a BIG movement of Blue Jays during the fall of 2018. The drop in acorn crops (see more below in the Barred Owl discussion), as well as beechnut and hazelnut, caused an irruption of Blue Jays southward. Because we see them throughout the year, many people don’t think of Blue Jays as a migratory species but there is an obvious “visible migration” each fall. The photo below is from 29 September 2018 at Point Pelee National Park in Ontario, a day when 13600 Blue Jays were reported in less than 4 hours.

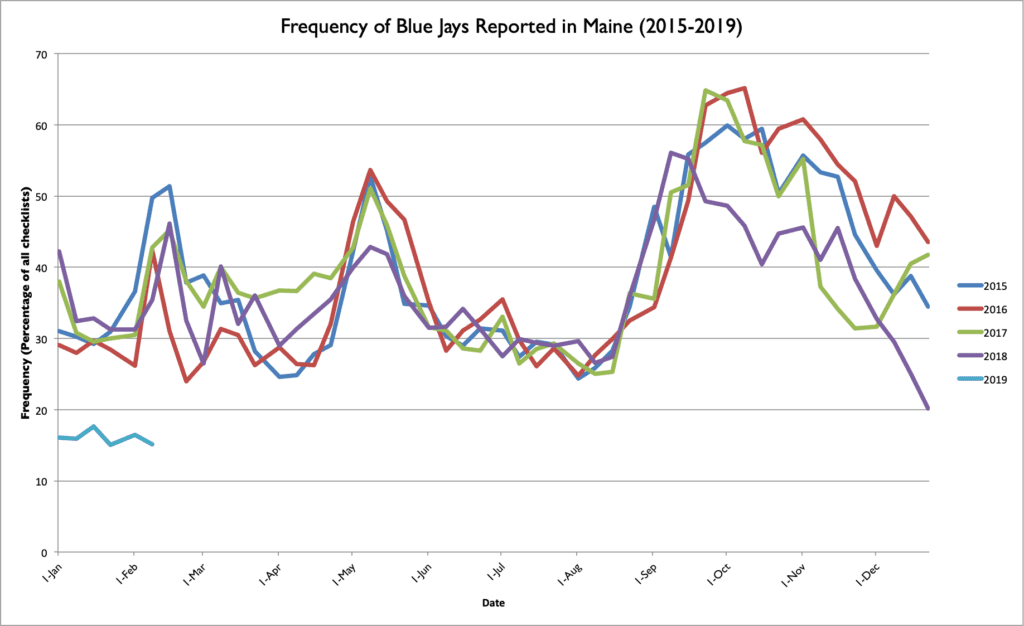

We can look at eBird’s Frequency Charts to visualize the movement and subsequent drop in Maine. We use frequency which represents the percentage of all checklists submitted that include the target species on it. A good thing about using frequency is that, as a percentage of all checklists, it is not biased by the number of checklists submitted, or the number of people submitting lists. You can easily see the drop in frequency, going well below the average occurring in the fall, around September/October, and continuing into 2019. The frequency, which had ranged 28-33% in the last four years is now holding steady around 15%. The same patterns is being seen in New Hampshire, but adjacent areas like Ontario and Massachusetts are not noticing such a decline. Going back in time, the last drop like this appeared during the winter of 2011-2012. Also note the significant drop in November of 2017, the last time people freaked out about birds disappearing.

Barred Owls

This winter is shaping up to be one of the best in recent memory to see Barred Owls. Owls have low detection rates, so it is not as clear to looks at eBird frequency charts, as we did with the species above. We can get a rough idea of the increase by add up individual reports this year and comparing the same period last year: From 1 January to 15 February, there were 129 reports in eBird during 2019, versus only 34 in the range during 2018. Again, this is not a perfect comparison as it doesn’t take into account effort (amount of hours spent or people looking). In that time period, there were 26% more checklists reported in Maine in 2019 than in 2018 (Keep up that excellent citizen science effort!)

On a cautiously optimistic note, there have been an unfortunate number of roadkill or injured Barred Owls reported but it doesn’t appear to be as high as we’ve seen in the recent past. The Press Herald reported in December:

In the past six weeks, the Center for Wildlife in York admitted 12 injured owls, roughly as many as the center sees in an entire winter.

“It has been an extraordinary year, from what we’ve seen. It’s all about that predator-prey relationship, that food-chain connection,” said Kristen Lamb, executive director of the center, Maine’s largest wildlife rehabilitation facility.

At Avian Haven in Freedom, a bird rehabilitation center just east of Waterville, co-owner Diane Winn said 49 injured barred owls were admitted between Oct. 1 and Dec. 13 – compared with nine during the same period last year. Ninety percent of the owls were struck by vehicles or found on the roadside, she said.

We don’t have updated totals yet but this is apparently better than the 2016/17 winter when over 100 Barred Owls had been brought to Avian Haven between 1 October and 10 February.

The assumption is that this Barred Owl influx is a result of a highly productive breeding season for the owls thanks to an abundance of prey, especially Gray Squirrels (and other rodents). You may recall the boom in squirrel numbers we saw last fall, with reports of them dispersing, making rare water crossing, as well as the overly conspicuous amount of roadkill. The large amount of squirrels are likely thanks to the recent years will oaks producing high numbers of acorns, a great food source for squirrels.

We also see irruptions of Barred Owls about every five years, so this winters increase is probably a combination of local and dispersing owls. It would be interesting to know how many of these birds are juveniles, but without close examination it is very difficult to tell the age of these birds.

Eastern Bluebirds

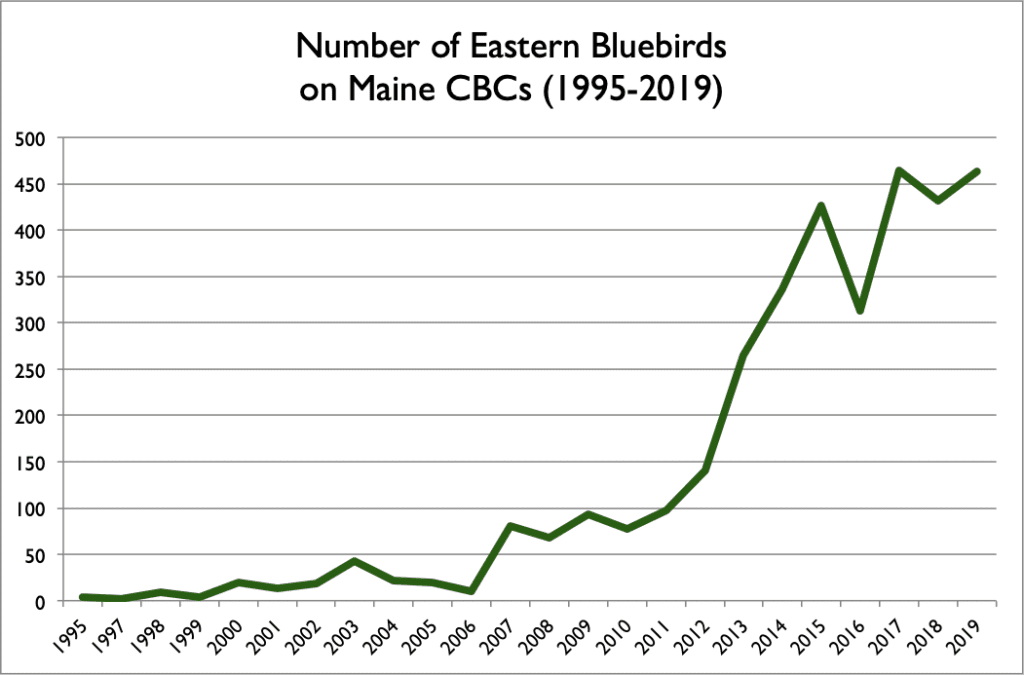

As a quick update to our 2015 “It’s Winter in Maine! Why do I see Robins and Bluebirds?” article, Eastern Bluebirds continue to be more common in the state throughout the winter. Below is a chart showing the number of individual Eastern Bluebirds seen on Maine Christmas Bird Counts, including “unofficial” results from this winter’s count. Note: This chart shows the count of individuals but an almost identical curve is shown when using birds per party-hour, meaning this is not biased by the number of observers.

This is only a snapshot of a few species we are seeing obvious changes in their frequency and abundance this winter. Let us know if there are any changes that you’ve seen in your backyards!

-Doug