Hello! I’m Emma Sloan, a biologist with Maine Audubon’s Plover Crew. We have spent this summer protecting the endangered Piping Plover along 22 beaches in southern Maine. As a new graduate and new resident of Maine, I have learned so much through this work. So, before the season ends, I wanted to share the lessons I learned from the plovers this summer.

1. Arrive Early

The first lesson I learned on the Plover Crew is that the early bird does indeed get the proverbial worm. In the case of Piping Plovers, pairs that nest and hatch their chicks early in the season are often rewarded with fewer people on the beach and therefore more space to raise their chicks. When Maine beaches start to get crowded around the Fourth of July, these early birds will have already fledged their brood and can spend the rest of the summer relaxing with the rest of the beachgoers before heading back south for the winter.

As a Plover Crew member, arriving early also means beating the crowds and, toward the end of the season, the heat. The earlier we get on the beach, the nicer the weather and the easier it can be to find birds foraging on the open sand without needing to weave among dozens of people. As someone who struggles with early mornings, there is nothing better than a meeting with such a motivated and enthusiastic crew of biologists to get me up and out the door. The reward of watching our plovers succeed in real time makes every early day worth it.

2. If at First You Don’t Succeed…

Plovers don’t give up. This summer I watched as many plovers repeatedly lost nests to high tides, predators, and, sometimes, to people. On one beach in particular, multiple pairs of Piping Plovers kept losing nests halfway through laying their full clutch. We suspect a family of skunks kept eating the eggs. Instead of giving up, these birds simply scraped out a new nest and laid the remainder of their eggs. All of these pairs successfully hatched chicks, even if it was just a single egg.

It’s impossible to work closely with these small shorebirds and not be inspired by their resilience. It takes dedication and flexibility to succeed in such an intensely variable place like Maine beaches. This statement applies not only to the Piping Plover but also to our work on the crew. On any given day, our crew manages weather, harassment of the birds (yes, we’ve had to tell adults not to chase plovers on multiple occasions), and balancing the needs of landowners, towns, and – of course – the plovers. It’s unusual for an endangered species to live so publicly and for field work to require daily outreach. But, the nature of the beach is unpredictable; it’s why I love this work.

3. Work Together

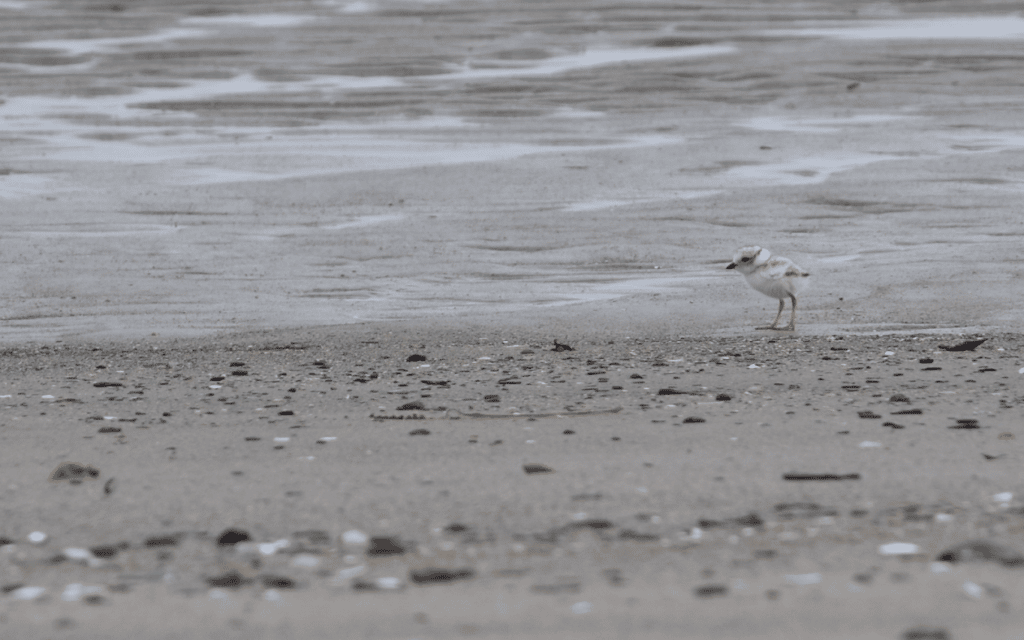

With a count of around 240 fledged birds, our crew watched a lot of plover broods grow this summer. Just like the families we see on the beaches, even plover parents show a variety of parenting styles. While I can’t scientifically attribute any specific style to success, it’s clear to me which parents have their communication down. Both male and female Piping Plovers take turns incubating their eggs. When the chicks hatch, both parents look after them while they’re young and vulnerable. Chicks hatch at under an inch tall and begin traveling down to the water to feed from day one. Parents keep a close eye on their chicks while feeding and, if someone walking the beach gets too close, the parents call to each other and move their chicks up to the dry sand. As soon as the perceived threat passes, the parents call again and accompany their chicks back down to feed. On busy beaches, parents do this all day. Their teamwork pays off a month later when the chicks first spread their newly-feathered wings.

Good communication is also key for the Plover Crew. Plover work in Maine requires handling a lot of knowledge and organization in a short amount of time. As I have said multiple times this season, we can’t control the birds, which means that we must make decisions fast on how to prioritize our limited time. I am so grateful to our wonderful director, Laura Minich Zitske, and lead biologist, Laura Williams, for their guidance. And yes, for those wondering, we have decided that Laura Zitske would be our plover mom and Laura Williams would be our plover dad.

4. We Are Not Alone

I didn’t know what to expect when taking this job. I only knew I loved birds and wanted fieldwork experience. Finishing this season, I continue to be inspired by the diversity and breadth of people fighting to protect one small, sandy-colored shorebird. Working in an environmental field can often lead to compassion fatigue. I saw it in myself and my team many times. But no matter how low I feel, knowing we are not alone–people or plovers–gives me hope.

It has been yet another record year for Piping Plovers in Maine. This success is a result of countless volunteer hours, landowner support, and collaboration with towns, municipalities, and the state. Thank you to everyone. We couldn’t do this without you.