The national birding community is still in the grips of Great Black Hawk fever. Those of us who get excited about seeing rare birds are still abuzz about this one, so far outside of the tropical range of this species and surviving the start of a cold Maine winter. After a few days’ absence, the Great Black Hawk was recently relocated near Deering Oaks Park. Keep tabs on the Maine Birds Listserv for the most recent info.

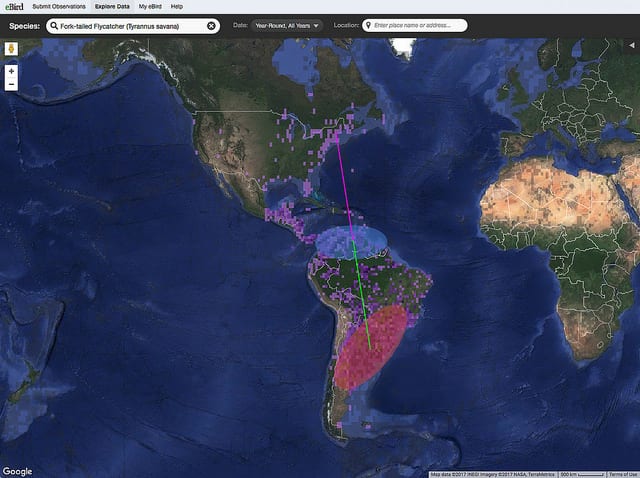

The Great Black Hawk is hardly the first rare bird to visit Maine in recent memory. In 2017 alone, Maine birders found a Fieldfare (native to Eurasia), a Fork-tailed Flycatcher (native to South America but seen on our Gilsland Farm property), and a Vermilion Flycatcher (southern U.S. and parts south). There are many more examples, each a delightful surprise for birders.

The recurring question is: why? What makes a bird fly so far in the wrong direction?

There is some good scholarship about these questions, much of it summarized in the excellent book Rare Birds of North America, by Steve N.G. Howell, Ian Lewington, and Will Russell, published in 2014. The book highlights nearly 300 “rare” or “vagrant” species seen in the United States, and speculates on how they arrived.

So why do birds show up in weird places? There are five common explanations:

- Drift

Migrating birds can’t get advance weather forecasts, and may be pushed off course by storms, strong headwinds, or other unfavorable conditions. A bird in the middle of a migration has a few options when encountering foul weather: turn back, fight on, or just let the winds carry them wherever they may. That last option can result in birds “drifting” far off course.

Some vagrant birds reach Maine by drifting across the Atlantic. Birds migrating from mainland Europe to the UK or from the UK to Iceland and Greenland may encounter storms with northeast winds which push the birds across the Atlantic to Maine or eastern Canada. The Fieldfare in Newcastle perhaps arrived via Atlantic drift, as other European species likely have, such as European Golden-Plover or Northern Lapwing.

Another type of drift occurs across the Atlantic closer to the Equator. Birds migrating from Europe to wintering grounds in western Africa might be pushed offshore by storms and drift all the way to Brazil. When these species feel the urge to migrate northward in Spring, they do so along the North American coast. It’s quite possible that the famous Little Egret that has spent several summers near Gilsland Farm in Falmouth arrived here after first coming across the Equatorial Atlantic.

- Misorientation

The internal mechanisms that guide bird migration are not fully understood. Birds don’t have GPS, but they somehow understand that they need to fly huge distances at very particular times of year. Migration is one of the most incredible of natural phenomena, but not all birds get it right.

For whatever reason, sometimes a bird’s internal compass is faulty, and they will simply migrate in the wrong direction. Instead of flying east, they’ll fly the west. Or they’ll fly north instead of flying south. Birders can often diagnose misdirection because the timing and the distance traveled line up with the bird’s normal migration, it just occurred in the opposite direction.

Gilsland Farm’s 2017 Fork-tailed Flycatcher might be a misoriented vagrant. Fork-tails often migrate thousands of kilometers between northern and southern South America in fall, and Maine is about the same distance directly north.

- Overshooting

Some birds simply migrate too far. Like I said: no GPS. Seen most commonly in young male birds, many different species overshoot their destinations to varying degrees. The majority of these species are lesser vagrants to Maine, such as southern species like Summer Tanager or Hooded Warbler. Though these birds do not come quite as far as, say a Fieldfare from Europe, they are still quite rare and are a welcome sight for Maine birders.

- Dispersal

A change in habitat or food conditions sometimes forces species to move far outside their normal ranges, a movement known as dispersal. In a drought, water birds like ducks or rails will disperse to find water. Unusually cold weather may force birds down out of the mountains and into lowland areas. There are many conditions.

Dispersal vagrants are frequently seen in Maine, especially in winter. Cyclic patterns of cone crops in northern Canada often force finches such as Red and White-winged Crossbills, Pine Grosbeaks, or Common Redpolls to fly south to seek food. These patterns are also called irruptions, and are eagerly anticipated (and forecasted) by birders.

An interesting example of dispersal occurred in spring 2014 when Maine had Brewer’s Sparrow, Western Tanager, Virginia’s Warbler, and ‘Oregon’ Dark-eyed Junco. These are all typically fall vagrants to the east but extreme drought conditions in California and the southern Midwest likely forced those species to disperse east.

- Association

Finally, sometimes birds of one species join migrating flocks of another, similar species. This can result in significant vagrancy when species from one breeding area return to different areas. For example, both Canada Geese and Barnacle Geese breed in Iceland, but the Canada return to North America for the winter while the Barnacle Geese return to Europe. If a Barnacle Goose associates with a flock of Canadas, it may return with them to the US as a remarkable vagrant. This happens frequently with geese and duck species, such as Barnacle and Pink-footed Goose, seen in Maine almost annually.

The question remains, however: What brought this Great Black Hawk to Maine? The answers aren’t so clear, as the bird doesn’t neatly fit into any of the categories above. For one thing, Great Black Hawks are not normally migratory, meaning that moving a great distance in any direction is unusual. So, it hasn’t overshot anything and it hasn’t drifted. It’s not associating with other birds, so that’s out. It could be dispersed from it’s native Mexico, though we aren’t seeing an influx of other species similarly seeking new habitat. It’s certainly misoriented but, again, that’s unusual in non-migrants. Whatever the real reason, we’re glad it’s here.

It’s impossible to know just when and where a vagrant bird will show up in Maine (indeed, that uncertainty is a big part of why seeing a vagrant can be so thrilling), but the mechanisms that bring these birds here aren’t such a mystery. Understanding patterns of vagrancy can help birders plan for birds showing up, and better understand them when they get here.